Welcome to episode 92 of The Way Out Is In: The Zen Art of Living, a podcast series mirroring Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh’s deep teachings of Buddhist philosophy: a simple yet profound methodology for dealing with our suffering, and for creating more happiness and joy in our lives.

In this installment, Zen Buddhist monk Brother Phap Huu and leadership coach/journalist Jo Confino are joined by special guest Jo-ann Rosen. Together, they discuss individual and collective trauma and how mindfulness and neuroscience can help address it. The conversation further explores the concepts of current and historical trauma, how the nervous system can become overwhelmed by modern stresses, the courage required to be vulnerable and honest about our suffering, how this can lead to deeper connections and understanding within a community – and more.

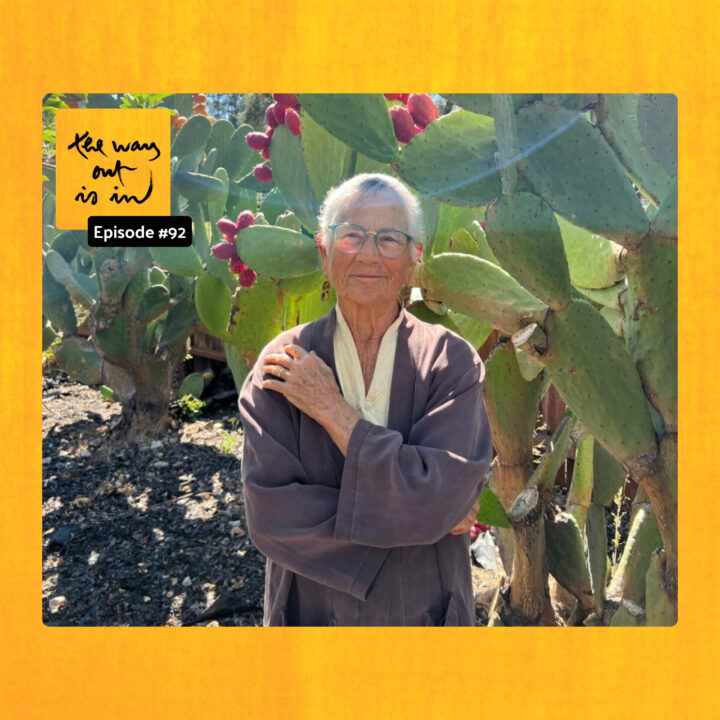

Jo-ann, a psychotherapist with expertise in trauma and mindfulness, shares her personal journey of discovering the Plum Village tradition and how it has informed her understanding of trauma. She emphasizes the importance of collective healing, drawing from her work with marginalized communities and the power of creating safe spaces for people to share their experiences and find support in each other.

Brother Phap Huu also shares his experiences of supporting the Plum Village monastic community and retreatants in cultivating stability and healing through mindfulness practices.

Bio

Dharma Teacher Jo-ann Rosen, True River of Understanding, Chan Tue Ha (pronouns she/her), received the Lamp of Wisdom (symbolizing the transmission of Dharma from Zen Master to disciple) and authorization to teach from Thich Nhat Hanh in 2012. She practices with the EMBRACE and Victoria Sanghas, is a licensed marriage and family therapist, and teaches and lectures internationally, focusing on inner stability and community resiliency. Her writings center on a neuroscience-informed and trauma-sensitive approach to individual practice and collective awakening. She lives with her partner of 40 years in the oak woodlands of Northern California, US.

Photo by Leslie Kirkpatrick

Co-produced by the Plum Village App:

https://plumvillage.app/

And Global Optimism:

https://globaloptimism.com/

With support from the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation:

https://thichnhathanhfoundation.org/

List of resources

Live show: The Way Out Is In podcast with special guest Ocean Vuong plumvillage.uk/livepodcast

Embrace Sangha

https://www.embracesangha.org/

Unshakeable: Trauma-Informed Mindfulness for Collective Awakening

https://www.parallax.org/product/unshakeable

On the Plum Village App > Meditations > Trauma Informed Practice

Interbeing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interbeing

The Miracle of Mindfulness

https://plumvillage.shop/products/books/personal-growth-and-self-care/the-miracle-of-mindfulness-2

Dharma Talks: ‘Redefining the Four Noble Truths’

https://plumvillage.org/library/dharma-talks/redefining-the-four-noble-truths

Thich Nhat Hanh: Redefining the Four Noble Truths

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eARDko51Xdw

‘The Four Dharma Seals of Plum Village’

https://plumvillage.org/articles/the-four-dharma-seals-of-plum-village

Quotes

“The nervous system evolves very slowly. It doesn’t change overnight. Ten thousand years is nothing in terms of your nervous system changing. So this nervous system I’m running around in is evolved for a hunter-gatherer. It’s not evolved for being in a car at a stoplight or having somebody demand things of me that I’m incapable of doing. Then I start to be nervous as if I’m going to die. That’s so bewildering. So as I learned more and more about the neuroscience, it was this great relief: ‘I’m not broken. I’m okay. I don’t have to hide what I can’t do.’”

“We’re all suffering from the expectation that we can function in this crazy world when our nervous system is not made for unrelenting stresses. And when we experience unrelenting stresses without good social support, our nervous system is overwhelmed and expresses that in a variety of ways. But the first line of what this neuroscience stuff can do is make us realize that we’re acting normally in a very tragic situation that we’re just not made for.”

“I really shy away from the word ‘trauma’, because it has a very particular spin right now. That’s not to say that deep-trauma therapists and super astute neuroscientists in labs and scanners, et cetera, aren’t making a huge contribution to the understanding of trauma. But I would like to take the word out and instead say, ‘We’re dealing with things that we’re not built for.’”

“To put it crudely, the nervous system creates certain states of mind that are purely about well-being – and we can savor those. But then we have certain states of mind which require more alertness and more activity in our bodies. That’s not bad; we have all the mental formations in there and can handle it without being carried away. And one of the things that neuroscience can bring to our understanding of Thay’s teachings is a little better sense of, ‘What does it mean to be carried away? How can I tell when I’m carried away?’ Because that’s really foundational in our practice.”

“Is our practice something that will heal traumas? Well, sometimes. And sometimes not. So it’s not an ‘either’ or ‘but’; what we’ve been working with is how to help ourselves regulate our nervous systems so we can practice, because practice is so much bigger than any trauma that we have.”

“Mindfulness means that you can be triggered, but know how to be with the emotions that are being triggered – so that you can be a part of the world, engaging with the world, engaging with yourself.”

“To walk together, that’s very healing. To listen together, to feel safe, that’s very healing. And that is teaching our nervous system the feeling of safety, to allow us to also touch our empathy. So, when we see others who are not in safety, we have empathy; we want to do everything in our capacity to transform that part of society.”

“There is no way to healing; healing is the way.”

00:00:00

Dear friends, welcome to this latest episode of the podcast The Way Out Is In.

00:00:21

I am Jo Confino, working at the intersection of personal transformation and systems evolution.

00:00:26

And I am Brother Phap Huu, a Zen Buddhist monk, student of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh in the Plum Village tradition. And before we begin today’s episode, I would like to share something very special. On September 12th, Jo and I will be recording a live episode of The Way Out Is In in London. And we’ll be joined by author and poet Ocean Vuong, who is a dear friend of mine and also admirer of our teacher, Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh and the Plum Village tradition. The evening will be a deep reflection on how we cultivate joy and togetherness in the midst of hardship, something we all need. And we really would like you to join us for this live event. So you can find details and tickets at plumvillage.uk/livepodcast. So please come and be there with us.

00:01:18

And also just a few days before, on August the 26th, Brother Phap Huu and I will be releasing our second book, which is called Calm in the Storm, Zen Ways to Cultivate Stability in an Anxious World. It’s a companion to these uncertain times and we’re happy to share our journey with you. You can pre-order it now and it will also be available at the live event in London. We hope to see you there. So today, we have a very special guest, Jo-ann Rosen, and we are going to be talking about individual and collective trauma.

00:01:58

The way out is in.

00:02:24

Hello, everyone. I am Jo Confino.

00:02:26

And I am Brother Phap Huu.

00:02:28

And today, brother, we have a very special guest who is Jo-ann Rosen, who I would say is a bit of an expert on trauma, but look at it in a very broad sense from neuroscience and mindfulness and how those can come together to actually work on this arena of life, which is becoming so important in so many people’s lives. So Jo-ann, welcome.

00:02:59

Oh, thanks.

00:03:01

And Jo-ann came into contact with Thich Nhat Hanh 30 years ago. So she is an elder in this community and she’s been a Dharma teacher for the last 13 years. So Jo-ann, it’d be lovely to know about the first moment where you came in touch with Thich Nhat Hanh and then Plum Village tradition. Can you just tell us a bit more about that?

00:03:25

Oh, sure. That’s an experience that is imprinted in my mind, because I was at a day of mindfulness, which I thought was a day where you just meditate all day. And I was still working on, working up to 20 minutes. And so we did the usual day of mindful things. And Thay gave a talk and he’s sitting on a kind of a makeshift stage in a big field. And then it was time for walking meditation. And he kind of floats down from the stage. And as he passes in front of me, I feel this like energy, like some big wind or some huge sound reverberating inside of me. And I go like, whoa, what was that? Because I had absolutely no spiritual or kind of woo-woo inclinations. So I had no notion of what I was experiencing. But I knew I wanted more. And so Thay was doing a retreat at a Jewish camp in the South Bay, in the Bay Area. And I signed up for that along with seven or eight friends. And that was never to return, that was a really super impactful retreat for me. I learned a lot. And I wanted to be a part of a community that wanted to be good. That was my hit on the mindfulness trainings. And from there, you know, step by step gave me a really different life than what I had expected.

00:05:42

Thank you, Jo-anne. And I am personally delighted you’re here, because for a long time, I felt that trauma is such an important… it’s not even a topic, it’s an important arena that I know hasn’t been important in my life. And it’s something I think he’s talked a lot about, but often with very little understanding. And I think you bring a very fresh perspective, because not only are you a psychotherapist, but you have an understanding of neuroscience and the mindfulness practices. So I’d really like to start by just, in a sense, you’re just giving a sense of what is it that this global society is facing in terms of trauma? And why has it taken up so much of your attention?

00:06:35

Maybe to go backwards instead of what are we facing? What have we got behind us? And to say that I am absolutely not an expert in trauma or in neuroscience. And that that first retreat was a real opening to me. The camp was a Jewish camp, and it had an exquisite memorial to the Holocaust. And I practiced touching the earth in that space. And all of a sudden, a whole lot of understanding came to me about my own anger and my own edginess and the trauma that my family had suffered, not from the Holocaust, that the myth in my family was that the Holocaust didn’t really affect us. Which was because most of my family was already dead from the pogroms. And so there wasn’t anybody left to be directly affected. But I had been very judgmental of myself for being wired too tight. Being too reactive. Being too much like my father. And in that moment of touching the earth, I realized that my father was just a recipient of a long line of horrible things that had happened. And that I was just the recipient in the next step. And that brought me a sense of compassion for my father and for myself. But I didn’t really encounter notions of trauma and neuroscience at that point. And I don’t remember exactly how it happened, but a number of things came together kind of simultaneously. Causes and conditions, of course. I was introduced to a healing modality called the community resiliency model. Actually, I was introduce to it the trauma resiliency model, which is a combination of understanding through neuroscience, but very simple, things that anybody, even little children, can understand. So knowing about your nervous system and then using the body to be a mindfulness practice. And I really liked this particular model because the community part was it’s very simple, once you learn it, you can teach someone else, and that person can turn around and teach someone else. And that’s what grabbed me because there is so much massive suffering in the world that I wasn’t so interested in how does one become more enlightened or more chance of being enlightened, as how does someone keep their nose above water and not drowned in the sea of suffering that isn’t just their personal suffering, but that their whole community is suffering from. So that got me interested and I started to learn more and more popular science, not deep, you know, knowing all the parts of the brain and what they do, but just to have a felt sense of what’s going on in my biology. And as I did that, a whole bunch of things fell into place for me. For instance, I could never follow my breath. And that in this model, you understand that maybe following your breath actually makes you more anxious depending upon how you put your attention. And so immediately I was like, oh, there’s nothing wrong with me. Looking at this through this lens helps me to see I’m normal under really abnormal conditions. When I say abnormal conditions, I mean that the nervous system evolves very slowly. It doesn’t change overnight. 10,000 years is nothing in terms of your nervous system changing. So this nervous system I’m running around in is evolved for a hunter-gatherer. It’s not evolved for being in a car at a stoplight or having somebody demand things of me that I’m incapable of doing. And then I start to be nervous as if I’m going to die. That’s so bewildering. So as I learned more and more about the neuroscience was like this great relief. I’m not broken. I’m okay. I don’t have to hide what I can’t do. And that we’re all suffering from the expectation that we can function in this crazy world when our nervous system is not made for unrelenting stresses. And when we have unrelenting stresses or great huge things without good social support then our nervous system is overwhelmed and it expresses that in a variety of ways. But the first line of what can this neuroscience stuff do is it can make us realize that we’re acting normally in a very tragic situation. And we’re just not made for that.

00:13:44

Thank you, Jo-ann. And I’m just wondering if you can talk a little bit about how trauma operates. And also in the sense, you talked about two things there. You talked about historical trauma. And you talked current trauma. So there’s some people who have experienced collective historical trauma and are experiencing trauma in the present moment. And I just want to… sort of get a sense from you how are we all traumatized? Do we all suffer traumas? Because one of the things I’ve always felt is that traumas don’t have to be major to be a trauma. They can be small traumas that affect us and big traumas. So can you give us a sort of… pry that a little bit apart and just give a sense of how trauma is operating on a sort historical and current function. Are we all traumatized?

00:14:40

Well, that’s a big word in our culture now. And everybody is perhaps clinging to, well, I have my trauma. So that’s my excuse for whatever it is I do. And it is. It’s an understanding of what I do, but of course we still need to take responsibility for it because it’s dragging us around and a lot of other people at the same time. I really shy away from the word trauma because it has a very particular spin right now. And that’s not to say that deep trauma therapists and super astute neuroscientists in labs and scanners, et cetera, aren’t making a huge contribution to the understanding of trauma. But I would like to kind of take it out and say, we’re dealing with things that we’re not built for. We’re having certain things that are overwhelming in our nervous system and that the nervous system, in a very crude way, and I think it’s good enough for this understanding, is to say we have certain states of mind that are purely well-being and we can just like savor those. And then we have certain states of minds which require more alertness and more activity in our bodies. That’s not bad. We have all the mental formations in there and that we can handle it without being carried away. And I think that one of the things that neuroscience can bring to our understanding of Thay’s teachings is like to have a little better sense of what does it mean to be carried away? How can I tell when I’m carried away? Because that’s really foundational in our practice. Do we have the capacity to put our mindfulness around our suffering and that when we do, we have all these practices to do it. But that is not right effort if we do not have the capacity. And maybe some people just don’t have a clue as to what that means. So this mindfulness state is when our nervous system can handle whatever’s happening. Maybe it gets a little more activated or a little less activated to meet the situation, but it’s, we know, of course, one perspective is not enough, but we’re able to see things more or less as they are and we can explore and be curious without being on automatic pilot. But there are times when our perception of threat is so intense that our nervous system just activates to meet the moment which is a good thing for a hunter-gatherer who has to outrun a saber-tooth tiger or play dead or to fight off some kind of snake that’s wrapping itself around your leg. But that’s an activation. It’s getting carried away by the nervous system, putting a lot of energy into our arms and legs to do what we need to do and then it’s over. And if we live through it then we can kind of shake it off and relax a little bit and have somebody go wow, I saw that and that was really hard. And I think you did a great job. Or here, let me give you a drink of water. But there are times when the stresses are unrelenting so that that adrenaline is pumping out, pumping out and it just starts to make a different default mode inside your body like you’re stuck there even when the threat is gone. So that’s what I would call trauma. And it can happen that you’re like really on high speed, lots of energy, mind going fast, not being able to think clearly feeling shaky, anger that you can’t control. It’s an automatic pilot. It’s whatever you needed to do under certain circumstances to keep yourself safe. And there are other times when your body is so depleted from all these stresses that it just like is numb or energyless or your mind is empty in a way that is not nirvana or that you feel numb, no feelings. So those are being carried away. And I would much rather talk about being carried away and to say that our practice helps us understand when we have the capacity and when we don’t. Because first foundation of mindfulness is to be aware of the body and the body is where these messages are coming from. So when we have the capacity we surround it little by little we see what it’s made of and there are ways to do that little by little that’s helpful. And when we notice that whoa, I really can’t do that anymore, then we go back to really watering those wholesome seeds finding joy, finding delight, finding safety, finding accompaniment and so that’s kind of a natural flow of energy. There are times when we’ve been watering those wholesome seeds, watering them, but stuff keeps coming up that you have no capacity to handle and it’s really interfering with your life. And then my notion of therapy is to find somebody who can hold the mindfulness for you while you are experiencing these things because you don’t have that capacity. And that’s when some kind of mental health professional or healing professional can be really helpful. So then the question is well is our practice something that will heal traumas? Well, sometimes. And sometimes not. And so they’re not an either or but what we’ve been working with is how do we help ourselves regulate our nervous systems so we can practice because practice is so much bigger than any trauma that we have.

00:23:13

Thank you. Phap Huu, none of this is a surprise to you because of course this is what you also work with day in and day out when retreatants, you have thousands of people coming here every year, many of whom come feeling exactly how Jo-ann has described sort of overwhelmed, burnt out, feeling that they can’t slow down and stop. And also, in a sense, the Plum Village monastics, in a sense, are in one aspect a bit like those mental health professionals which is providing a grounding of mindfulness in which people can show up. So as you listen to Jo-ann, you know, what does that bring up for you in terms of your experience of all these thousands of people you see year in and year out. And whether that you see that almost getting worse, getting more significant in terms of people’s feeling of overwhelm.

00:24:14

That’s the suffering that we all share, being overwhelmed, and when you were sharing, the first thing that came up to me what Plum Village offers, it offers a collective space of healing. And I think this is something that is also very unique in the Buddhist culture which is a sangha, a community. That our healing is not an individual journey but it needs a collective support system. It’s a technology. It’s a way of relying on other people’s mindfulness, seeing other people’s kindness, and feeling safe. And in today’s conversation I had with a friend, he just finished a retreat that Jo-ann was a part of, which is the retreat for scientists. And one of the retreatants shared to him that is the first time she’s been in a community or in a space with over 200 people on a daily basis that she feels absolutely safe and that none of her nervous systems were always active and that is very unique in today’s world because the culture that we live in now it is overstimulated. And when Jo-ann was sharing like I was agreeing to so many of the of the insights that Jo-ann was sharing and I was just nodding my head and one of it is realizing like how much of our senses that we are encountering through the news, the information, the technology. And I don’t think that we were built for this. I think as a human we are part of the cosmos ecosystem. And we have our limits and we have a capacity of deep connection to the earth, deep connection to each other, deep connection to silence, and our culture now doesn’t allow that because it tells us we’re not enough buy this, wear this, listen to this, hear this. Did you hear about that? You know, even I sometimes feel a lot of FOMO, like am I up to date? Am I up to speed with everything that is manifesting in the world? I’m not saying that we shouldn’t be engaged as, you know, our tradition is to be engaged and to be aware as mindfulness is to be aware. But mindfulness is also our compass to awaken us to say that’s enough Phap Huu, take a step back and do walking meditation. And we’re in right now, as we’re recording this podcast, we’re this period of lazy days to rest after the retreat and we’re preparing for the summer opening that will be coming in just a few days. And I find myself not having anything to attend to as in a formal schedule. But there’s many little things that I can attend to and I find myself putting on headphones and listening either to a soundtrack of melodies or even if it’s a soundtrack of Thay’s Dharma talks because it really calms my nervous system to hear my teacher’s voice. But today I had a realization, I’m like, no, I need to just listen to the nature that is present. And, in a way, if we look back at many many many years ago, like even generations ago, like we know how to do that. We knew how to take refuge in the present moment, in nature, to the insects, to the little creatures that are all around us. But now because we’re not living in relationship to nature we’re living more into relation with concrete and advertisement and the nuances of our world today, we are so afraid of the natural wonders that are there. So part of the retreat, and part of our collective healing and in the later years, our teacher, he was always an environmentalist from the very get-go. Like Thay was always teaching us to be aware of how we consume, what we wear, what we choose to support, because our resources that we’re spending on something is creating a system. And so, looking back at our present moment, now I’m also like I’m so happy that Jo-ann shared this because I’m also becoming allergic to the word trauma because people are using it, I’ve heard it as an excuse. People even challenge us at the monastery that what you said was triggering. And I said, well, the Dharma could be triggering in order for you to just recognize suffering. And in this time where everything is so individualistic, it’s like me me me, like my emotion, my feelings, which is important, like it’s very important because that is the the second establishment of mindfulness is to be aware of the feelings, the mental formations, the functioning of it which turns into habits which makes us say and do things and behave and have particular attitudes. And mindfulness is to shine light to it and see, this is what I do when these seeds are touched. But now we’re also becoming afraid of our own seeds. We’re becoming afraid of also being engaged with other people’s seed, because oh, that’s triggering me. But mindfulness is very different in, well, I wouldn’t even say mindfulness as a buddhist monk. I’m entering into spaces in order to hold and to listen to suffering. And the word trigger is also something that I’m skillfully using it now more and a lot of people have overused that word, trigger, and when you overuse it without essence and without respect to it, it loses its power. There’s a story where in the Buddha’s time, there’s a gentleman who’s always lying and he likes to lie because he gets the people’s attention. And he lies about the barn being burnt and everybody comes and then actually when the barn is burnt nobody came because he’s like, this person has a habit of lying. So it’s also like when we are too quick in like jumping on our emotions and running away and telling people to not engage with us and so on, I feel we have to be more responsible as Jo-ann has shared. And responsible, oh, I’m speaking this, I don’t want to be critiquing, because I see this in me, myself, and I’m learning to be very responsible and to… It’s almost like the ultimate concern and the daily concern, like there’s some daily fears that I still have today but that is not going to stop me from engaging in daily life. Right? But mindfulness is like oh, but when I am, my well-being is not fully equipped and it’s not healthy, then I understand my limits, I understand oh, if I stay in a room where these seeds are touched all the time, I’m going to become a little bit toxic, so then I want to come and I want to take care of that. So I just bring this up because last year I was challenged by people telling me like they don’t want to be in spaces because they’re being triggered in a retreat. And I was with another brother and we listened very deeply to the sharing but then the brother shared something that was really enlightening and the rest said, well did we ever, did we write in our description of a retreat that you’re not going to be triggered? But it’s actually mindfulness engaged, mindfulness is you can be triggered but you know how to be with the emotions that are being triggered so that you can be a part of the world, engaging with the world, engaging with oneself, in oneself is the world. Right? It’s, for me, when my body is reacting I know how to come back to my body, I can use mindfulness in my palms and I can put my palm on where the muscles or the body parts that are being tensed up and we all have different reactions and we all have different elements and places in the body where get stimulated and for me this has been… I still practice the first establishment of mindfulness, coming home to the body, in the body, because that’s where I am feeling the emotions that arises and how it becomes reaction. And in a retreat I think what I enjoy in Plum Village is we are doing a lot of collective trauma healing without that language. You know, to walk together that’s very healing. To listen together, to feel safe, that’s very healing. And that is teaching our nervous system of the feeling of safety to allow us to also touch our empathy because this is what it feels to be in safety. So when we see others who are not in safety we have empathy we want to do everything in our capacity to transform that part of society. So for me I understand with the lens of Buddhism that traumas are sufferings and the first noble of truth is to understand and accept our suffering. And to accept it with a smile. And I was also very critical and judgmental of my own self and of others in the community, of my elders, I’m like, why are they still suffering? You know, they’ve had so many years with Thay, they lived next to him. How can they still be so unstable? But there’s so many layers to everyone’s story that when I can be in touch with my own sufferings I have empathy. I’m like, ah, you know what, I’m luckier than them. I didn’t have to go through the journey on a boat. I didn’t have to through refugee camp. I spoke English when I was growing up. They didn’t speak English, they were probably mocked at. And we all have our different experiences. And those who suffer from starvation, those who suffered from a broken family being on the receiving end of the bullies, and so on. So we all so many different stories and part of the collective, the power of collective sangha is…, sangha means community, dear listeners, is that we get to expand our understanding of suffering and the stories that we can tell and that we listen to it impacts us so much, it gives us empathy, it gives connection, it allows us to interbe. And just this one thing before the story I had… I was really proud of myself when I transformed or I recognized one of my sufferings as a young monk and I was so proud of it I felt like oh, my god, after four years I have deep insight. And it was just recognizing one of my fears is because I was on the end of receiving the violence and the abuse of bullies that gave me a different way of being in the community even with monastics even though they can be the kindest person I had different reactions around them. And I had stories that I would create and so on. And when I realized like oh, these are all just stories, and these are like the past becoming alive in the present. And I have now the awareness oh, my dear five-year-old, you’re very different now, you can protect yourself and let me heal you, let me take care of you. And so I go and I tell Thay in this hut, I report to him. And I’m like sitting over there and I’m like, Thay, I want to share with you this deep insight. And Thay is so compassionate listening. And after I expressed like my realization he didn’t even congratulate me. He said, that’s why we practice. And I felt so defeated by that sharing of Thay, because if anything I felt like huh, I didn’t get the approval, the validation from my teacher. But if anything, he just gave me the validation of and this is where the Dharma comes in. And I remember leaving the hut very disappointed because I thought I would have this amazing wow moment with Thay and he was such a zen master, he just looked at me, and said, and that’s why you practice. Until now I’m very grateful for those words because if he said amazing, Phap Huu, you did it, you fixed yourself, I would have been caught in that moment. And as I have also experienced and seen that suffering and pains and traumas they take time to heal and the healing that I felt 10 years ago, 15 years ago now are still in the process of healing. And my inner child it’s actually very well, but there are moments it can still come up, it can see cry very loud. But now I’m not scared of it, I don’t enter into sorrow. If anything I can trust my own capacity to water the good seeds like what Jo-ann was saying, like in Buddhist language that is right diligence to nurture our mind. How are we cultivating our daily life? What are we watering? What are we practicing? What are we watching? What are we eating? And all of this in terms of Buddhism, I see Buddhism is such a rich culture and a rich tradition because a lot of the language of trauma healing it has been there for thousands of years in Buddhism.

00:40:04

Thank you, Brother Phap Huu. So, Jo-ann, you know, the heart of your work is about collective healing rather than just individual healing. Can you just build on what Phap Huu said from your perspective of how do you see the collective as being so important? And you have worked with a lot of marginalized communities so it’d be really wonderful if you could also share, you know, how has this suffering shown up in those communities? How is their collective response? And what difference does that make?

00:40:48

Well, Phap Huu, you said a lot of things and I can’t jump into that without responding a little bit to those things because there are some people whose natural tendency is to see the suffering, to be gung ho to, you know, hang in there no matter what, they’re going to meditate for 12 hours, they’re gonna, especially when they’re new here, they’re gonna come and they’re doing extra and they may not have the capacity to even know when they’re suffering because their style is to white-knuckle it and take their mind away or their attention away from their body so that they don’t suffer. And then there are people who go in the other direction, those people that you were saying they’re triggered and really there’s a difference between triggered and carried away and being on an automatic pilot where your nervous system is completely dysregulated and being uncomfortable and unaccustomed to handling those sensations. And I think in the first world there’s a huge push towards comfort and that comfort and safety get misunderstood, get conflated, and so learning how our minds work with little tiny issues like don’t move, don’t scratch, when you’re sitting, you will find out, you know, a huge amount if you don’t scratch. And then little by little their ability to recognize that they’re uncomfortable but they’re still safe increases and so I wouldn’t put everybody in the same category when they say they’re triggered. And we are in the business of creating resilience which is you notice the sensations in the body but those very same sensations that very same amount of sensation no longer carries you away, and that’s a very delicate and sometimes long-time project and we don’t want to encourage those who white-knuckle it to do that. And at the same time we want to encourage those people… Mindfulness makes us very sensitive, but that’s only a half of the healing it needs to make us sensitive and tolerant of those same sensations and so there needs to be an understanding of that and there are certain circumstances in which I think it’s completely appropriate that people cannot relax enough and be mindful enough in the presence of certain triggers to begin to work on that. So, you know, you give them somewhat of a safe space in terms of a cultural refuge or a place where they can relax enough and have confidence that those that they are with will not judge them or worse. And that we have human limitations but we also have extraordinary mind-boggling parts of our nervous system that we’re taking advantage of all the time that we don’t even realize. So if somebody comes up to me and they’re smiling so nicely but you don’t have a really sense that that smile is authentic, there’s no way my body relaxes. I begin to what’s called co-regulate with that person, my body is mimicking their body and when I feel that configuration around my face, I’m not feeling friendly. Maybe I’m feeling condescending or whatever but I have a sense that I am not safe with that person because they’re letting me think that they’re nice but they’re not having good feelings towards me. So I need to be in an environment where people are not judging, where people don’t have anger or preconceptions about me in order for me to share and be witnessed. So I think there are times when it’s appropriate to have some kind of refuge for our, for instance, for our Dharma sharing or for a retreat. So on a semi-collective level we have this practice of Dharma sharing and Dharma sharing is to share what’s on your heart, what you’re encountering in your practice. And to be able to share it in an environment where people are receptive, non-judgmental, mindful, caring, compassionate, and then our bodies relax as we tell about our difficulties. That’s healing. That is watering those seeds that have been wounded and making them stronger, and little by little that is fundamental healing. And sometimes, often, we can do that. But I think when we really push it, we run the risk of re-traumatizing ourselves, of being with those kinds of feelings, the mental formations, the bodily sensations, just get more. They’re giving the nervous system the message that you’re right, we’re unsafe, we need to keep doing those same habitual things. So that brings up the issue, you know, the practice has all the foundations for healing us, but we, as lay people, don’t necessarily have teachers or mentors and we’re practicing at home and so it’s important somehow to have that kind of one-on-one understanding relationship with somebody who can help guide us and help us discern when we’re overdoing it, when we are underdoing it, and to learn to be really honest with ourselves. If we tend to be somebody who really likes to hide out in the very wholesome, lovely feelings, to push ourselves, to stretch a little bit. That if we’re not stretching a little bit, we’re really not practicing, we’re not going to be able to understand on a bodily level what it is to transform our suffering. And if we’re somebody who’s constantly stretching too much, we can injure ourselves, and that we need to know the signs of that. And that that’s also something that in our offerings and embrace that we encourage people to know about but not get all uptight about, they’re not things that happen all that often.

00:49:32

Maybe what I want to share more while listening to Jo-ann, so people don’t get a wrong perception about Plum Village and our retreats. Everything is an invitation in our retreat. Nobody is forced to do anything. If you don’t want to wake up for early meditation, go to sleep, sleep as much as you need. And if there’s an activity that we offer that is maybe challenging maybe from a religious part or from a spiritual dimension that may be very new for us, I always, in my Dharma talks, in orientation, I always say everything is an invitation. If you’re uncomfortable, you can always step out. That is true. But at the same time, part of life is also being engaged and being open to an experience, being open, like you said, to stretch to our pains. You know, like physiotherapy, most of the therapy is very painful, but if you don’t stretch there, those muscles will never be re-developed or re-healed. So that’s why it was very difficult for me to say what I wanted to say skillfully but I always respect everyone’s suffering. I respect… Actually, I’m a very sensitive person. If somebody is in pain, I even say you can leave Plum Village. Don’t suffer here, don’t create this as a prison for yourself. But it’s also like, for me, I guess what I’m learning is not to use suffering as an entitlement for people to change their reactions, their truth to life. And I had to learn to not to white-knuckle because as those who didn’t have much in life we had to white-knuckle through everything. To be seen in school, I wasn’t a white person. I wanted to be seen. I excel in math, for example, it’s a very regular stereotype of all of us, Asians, but hey, I can do some numbers. And there are moments that the white-knuckling also just led to us understanding where the harm we were doing to ourselves. And if I have never white-knuckled myself, I don’t think that I would also understand what resilience is and I wouldn’t understand the suffering of my parents, for example. And in Buddhism like the middle way is always the safest way is to dance between the extremes of both sides which is, I fully agree, there are those who don’t acknowledge their suffering. They will never grow. And I’ve seen this in my community. I’ve see this in my siblings. And it pains me sometimes when I see that they can’t touch their true suffering. One time in my room we played a card game and in the card it has questions, it says to say one good thing about your mother and one good thing about your father and one thing that your father did that hurt you and your mother did that hurt you that you’re still caring today. And this brother can only speak about his father and cannot say anything about his mother. On both sides, the good and the bad. And he’s a Dharma teacher, so over 10 years in the monastic life. And for me in that moment, of course, I don’t want to push him and I was seeing how uncomfortable it was for him, how awkward it was for him in the setting of a community. And the sensitivity around the brothers and sisters that were in the room, we were so sensitive that we didn’t want to shame him and we didn’t push it. We were all just acknowledging that there are some sufferings, that the Dharma, we’re not yet there. And we have to give the right space, the right time to it. And for me when I get to witness that I can touch interbeing, his suffering is my suffering. And I really wish that he can touch this because it will unlock something in him. And in the relations of communities and of being together, whether it’s one-on-one or even by myself, it’s important to have the ability to be kind to the feelings that we have within us. And I can say this now, but many years I couldn’t say that if anything I always wanted to white-knuckle it. And one of my causes of that was just to be seen as a person of color. And that’s a reality, that’s the truth. And maybe that is a part of me because I have fought so hard so when I see those who don’t fight I’m like, you spoiled brat, you have no idea how lucky you are. And I’m just like, please, just like don’t be so entitled though, like don’t, you know… And that’s where it’s coming from. And I just wanted to, you know, just really emphasize. Because the danger of these podcasts and of these things you only hear one story, one time, and it creates a whole truth to each and every one of us, so excuse me for jumping in so quickly, Jo, but I felt like I just that was very alive for me and I just wanted to say that.

00:55:36

Thank you, Brother Phap Huu. And, you know, coming up for me is just this is such sensitive territory because there’s sort of, you know, in my life there’s the collective trauma of the Holocaust and of however many thousands of years of Jewish history and there’s my own individual suffering. And in a sense I feel this is a lifelong journey, it’s not something that is going to happen today or tomorrow, it’s something that is there and and present and there’s something for me about just giving it time and space and love and tenderness and not to fall a victim to it, but not to feel the need to solve. It’s just to be present for it and as long as it needs to be there. Jo-ann, and I just want to come back to collective side of things, because you had a beautiful politician’s answer saying I will answer that but actually first of all I think it’s relevant to say that…

00:56:44

She’s gonna do it again. Yes, I love this.

00:56:47

I’m not gonna let you get it over with this time.

00:56:51

It’s an invitation, right?

00:56:53

Yes, everything is an invitation.

00:56:56

So my invitation to you is to come back to this idea of collective healing as opposed to individual healing, because, in a sense, that, you know, Plum Village is collective healing, it’s bringing together, it’s not someone on their own doing it, it’s a community that is itself healing and inviting people in to heal. And as I mentioned earlier, you’ve worked with marginalized communities, so you’ve seen a lot of collective suffering held and also worked with groups, so I just want to, in a sense, explore how you see collective healing or collective whatever word you choose to use for it. And you can say something else first. If you need to.

00:57:53

Maybe a little collage of things. One is I really resonated with the wanting to be seen and especially a person of color in an all-white space and the sense of entitlement that some people have and how that can be a button and to say that that’s also common to me. And most people who suffer traumatic circumstances that create this locked-upness in the body eventually work through it enough to have what’s called post-traumatic growth and like the vast majority of people at least up until the point where they did this study, of course, now we have such snowballing of trauma situations, but when the whole community is traumatized all at once there grows both a resilience of people helping each other and going beyond their personal needs to give a hand to each other. And that every group that suffers a group trauma, that becomes part of their culture whatever the resilience is and also whatever the cautions are so that culture really is a collage of the collective trauma and the collective resilience of a people. And so often we only experience our own personal rendition of the collective trauma and we think oh, it’s me, and I’m the only one, and that there’s a shame, so we hide it, or at least we think we hide, we often do things that make it worse, but that it keeps us with this illusion of separateness and of it’s my fault, I’m damaged, I need, if I want to be a part of the group, I have to hide it. And that that destroys any possibility of healing, especially when it’s a collective trauma. And that when people can come together and share their individual experience and discover, oh, I feel that way too, there’s a power that’s released. And if it’s held in a space that’s non-judging, that’s calm enough, so that people aren’t co-regulating and getting carried away, and that that happens in a sangha, and it happens over a period of time, and often there are sanghas that are just all people of color, or all people who are dealing with a physical challeng, or people who, whatever. And that that creates enough safety to begin, and then little by little they have more and more capacity to do that same thing in mixed spaces, which I think is really important. But what do you have in mind exactly when you want me to talk about collective healing?

01:01:50

No, I think you are in that space now, which is around how do we heal together, and also how much being in a community of healing is about learning about the trauma. Because I know with my family, my mum and dad never talked about… My mother came out with a, you know, escaped the Holocaust, my father’s family were forced to flee from Bulgaria, but it was never discussed. It was hidden. And I always remember, I attended, when I lived in New York, this was nearly 35 years ago, there was the first international conference on the children of the Holocaust. And where they were just sort of really getting into this understanding of how trauma is intergenerational, how it gets passed. So for me, I was brought up as very English, and it was all hidden from view. And so part of the collective healing for me is about the understanding of what the trauma is, what the suffering is, because if we don’t understand it, then we’re just going to repeat it, and most likely project it onto other people as we’re seeing happening in the world. So where I was going, where I was hoping to go to in this was… as communities, understanding the suffering, and then healing together. And I know that’s, you know, a lot of your work, and you may want to talk a bit about your Embrace Project in relationship to that. That’s, I think, where I was hoping to go.

01:03:36

My own personal story, which is like everybody else’s story on some level. My grandmother lived with us. She escaped the pogroms in Eastern Europe at the turn of the 1900s. And she and I shared a room. And I have no idea where she was from. I have not idea what her circumstances were that brought her to the United States. Nothing was ever mentioned about the old country. And there was nothing ever mentioned in my family about anything that had to do with difficult feelings. So we never asked questions of each other. I didn’t even know I had an inner life until I was in college. You know, this seems like astounding. But I never learned to ask questions because questions were not permitted. But was that an individual trauma or was that a collective trauma? Because there was no skill set in our community for dealing. And also, people are immigrants. They’re busy trying to keep their nose above the water. And there’s not a time to like, look at your feelings. So there’s a whole group of people who are traumatized. They don’t even know it. This one’s so angry and this one never says a word. And so really being able to see the impact on a community. I was working with this model in the West Bank. And I was working with a group of Muslim women, quite traditional, all covered. And they all had children in prison, in the Israeli prison. And we were talking about, in different terms, how to water the wholesome seeds. And they wanted nothing to do with it because they felt it was a betrayal of their children if they were to be happy. And that they needed to hold that same suffering. In the meantime, they were depressed. They were not functioning. They weren’t being able to support their children in prison because they were being traumatized besides the trauma they were living, kind of secondary trauma for their children. And when they started to learn about, it’s okay to like water these wholesome seeds and to find out what do you do to blow off steam? And what do do you that you find that’s funny? And then one woman said, I take a paper bag and I blow it up and I make a really big sound. And the next day, we all brought in paper bags. And at the count of three we all popped the paper bags at once. And there was such energy in the room of one woman bringing something that allowed her some release that was safe to the whole group that was so far beyond popping a bag. That there was a sense of power. First with that woman and then with other women, they began to bring in sweets to our meetings. They began to heal each other. But they needed permission to feel good and see that that was actually a benefit to the community. And as soon as it was a benefit to the community, then it was okay. That it wasn’t an individual matter. So maybe that’s one small example of community healing.

01:08:28

Thank you, Jo-ann. And Phap Huu, you know, we often talk about Plum Village in terms of retreats and all the retreats that have come, but Plum Village is a monastery.

01:08:38

It’s a home.

01:08:39

It’s home.

01:08:43

We live here.

01:08:44

And you’re a group of monastics who have your own community and your own healing, which is not separate from the healing of the retreatants, but has its own sort of orbit. And so just picking up on what Jo-ann’s just talked about is how the healing happens within the monastic community. Because, of course, every monastic who comes to Plum Village has their own suffering. Has their own story. You are a mix of many cultures, many nationalities, different ethnicities, different genders. How do you see that? How does the monastic community work in terms of dealing with past individual and collective sufferings?

01:09:35

Well, suffering is the name of the business of Buddhism.

01:09:38

Without that, you’d be without a job.

01:09:42

We wouldn’t be Buddhist because that’s the first noble truth. But it’s true. But before we touch suffering, I think one of the uniqueness of Plum Village, of our tradition, is we actually first learn to touch joy and happiness. And it’s very difficult for many people, but this is not from Thay, this is from the Buddha himself. The Buddha was very particular and scientific on this. It’s almost like the Buddha said, if we want to go to surgery to take care of the pain and the wound, we have to make sure we are strong and well enough. We have to heal the words joy and happiness because I think joy and happiness has become a very narrow view on it. It’s like happy hippies and la la lands and, you know, like smiling, everything is going to be okay. No, we know there are things won’t be okay unless you actually get in and do the work, right? But the joy and the happiness that we aspire and make a vow every day to train is in the morning to bring joy to one person. And that one person can be you. And that joy, it’s in the term and the tradition of Plum Village, that joy is already the moment we wake up being able to know that we’re in community. That’s a joy. It’s a state of mind. It is… See that we can touch to give us a source of foundation of how we’re going to engage today. And happiness, it’s like, I’m well enough. I’m not perfect. No one is perfect. But I am well enough to eat, to listen, to learn, to experience. Like these are the joy and happiness that we aspire to engage in, right? It is a kind of gratitude. I think all of our joy and happiness equals a deep gratitude in the tradition when we deepen our joy and gratitude. But then on the daily life, there is a joy of being together. There’s a joy in working together, studying together, singing together. I know people get so shy of singing in Plum Village. It’s the first thing you learn is like, we’re going to sing a song and everybody’s like, what is this, kindergarten? Even our songs, it sounds very childish, but they’re actually very deep insights of Buddhism. But it’s very intentional the way Thay has set up our community. We learn to sing while we are gathering, or else just standing there looking at each other is so awkward. There are techniques that we have added in. And the singing is more deeper because as a child, maybe we have been lullabied by our mother or father. And melody has a very specific place in our hearts. But most of us, we have pushed it away. There was a retreat, like there’s this really old gentleman in my Dharma group and he looked, I couldn’t read him. He was, I didn’t know if he was having a horrible time in Plum Village and like torturing himself, or he’s having an okay time or an amazing time. I couldn’t read him. But on the last day, I would say, okay, this is our last sharing, so maybe we just get into the sharing. And he’s like, no, no, can we please sing? And like, what song would you like? He’s like Happiness is here and now. And I was like, wow, you can’t, you can’t what’s that saying? You can’t judge a book by its cover. And I was definitely, I was just afraid, my perceptions were like, oh man, how is this person experiencing his time in Plum Village? In Plum Village, the spacing for holding our pain and suffering is everyday. And we want to engage it in every action. It’s not like, oh, my suffering is here. I’m going to sit away from the sangha now. No, no, you’re suffering. Come and walk with us. You’re in pain? Push yourself to the meditation hall. Thay, our teacher, instructed us, when you suffer, that’s when you practice deeper. And drag yourself out of your bed and you get to the meditation hall because the collective energy of the community. What do we mostly do when we suffer alone? We go down a dark rabbit hole and we drag ourselves into despair and suffering. And we have to bathe ourselves in the collective energy. And that is how we learn to see the process of healing in every minute. The healing in Plum Village, in terms of the language of our tradition and our teacher, he said, there is no way to healing, healing is the way. That means the embracing of it is healing. The being with it is heal. The engagement of it, the joy is healing, the singing is healing, the transformation is healing. Your transformation, Jo, is my healing because there’s an interbeing there. Jo-ann’s elder stability is my healing because I can see, you know, that’s where I can grow and develop too. It’s not in our tradition, you don’t divide things. Sometimes people get mistaken by Buddhism because we love this because that’s how all of the teachers were able to teach because we need to combine them into brackets, into canons, into books and columns. They are just the finger pointing to the moon. But the process of enlightenment or the process of healing, it is already being in. Like for me, like during my crisis, the most powerful healing was just me sitting with the community. And I tell you, like those sitting meditations were some of the toughest sitting meditation because my pride, there’s a pride to suffering. My pride to suffering is like… I’m suffering, they’re not suffering. They don’t understand me. I’m struggling. Why is he smiling? Right? And like I am sitting there and my mind is screaming at me, telling me to get out of Plum Village. And I’m just like, no, no, this is where you take refuge. And it was like taming a tiger. This tiger was loud. It was restless. It was strong. It was wrestling me. And I just keep hearing Thay’s word, stick to the sangha, stick to that sangha, stick to the sangha. But in those moments, I had limits. I was a Dharma teacher. I was still the abbot. I remember Brother Phap Ung, one of my elder brother, said, Phap Huu, I think it’s time for you to give a Dharma talk. You haven’t given one. You’ve been a Dharma teacher for many years. And this is where my limit comes in. I said, dear anh, anh means elder brother. I can’t. I’m struggling. And I will be faking it up there. And I’m honoring my suffering. I’m honor my crisis right now. So there’s a difference between running away, being carried away fully, but still being with it, and then not also fooling yourself. And I could have said, yes, I’ll give a Dharma talk, and try to bypass it also. But I felt being in community, one of the things that I’ve learned is everything I do for the community, I want to do it, we’re authentic. Because that’s a representation of my community. So when I offer and when I give and when I am in service, I really want to do it in the capacity of this is a space of interbeing. I’m serving because it’s not for my pride, but I’m serving because there’s something I can transmit to people. There are some of the healings that I cannot heal yet, but every time I give a teaching, it is to teach myself. There’s still work I need to do. There are still places of understanding that I can expand my mind. Like listening today, I see my shortcoming, I see my limitations, I see my own triggers, and I want to expand myself more and more to mental illness or I don’t know if there’s a better word for that. My father went through deep PTSD and he’s a monk. I had to go home. I had take care of him. And we journey through this together. And now he’s very accepted of his capacity. He’s not running after who he was in the past. And he shared with me in a recent conversation on a phone call, he said, dad is just practicing Thay’s Dharma, and that is to dwell happily in the present moment. And now dad doesn’t have to be well like he was in the past. Because in this moment, dad is still able to offer something. It’s different now. So it’s accepting the new also. And my dad’s been teaching me a lot about PTSD and suffering and joy because he has so much joy now. And he has so much gratitude to life. And sometimes when he calls me, he calls weekly, so sometimes it’s too much. But sometimes I can’t wait for his call because it’s a boost of gratitude because he’s so grateful to life so there’s so much to learn. And there’s much to… So in the sangha, coming back to that, your question is, giving permission is very difficult too. Giving permission to oneself to suffer, especially as monks and nuns. Sometimes the perceptions that people… that we have created for ourselves because of people’s maybe reverence to us and so on. We’re not superhuman. We have so many feelings that we want to be in the feeling of. Recently, there was a brother who was going through a crisis and he wanted to run away. I want to leave. I want go and have time for my pain and suffering. And I was so proud of the community. The community said, yes, brother, and you stay in the community, what do you need? We’ll give you all the space you need. Isn’t it because we’re monastic, this is why we’re here, is to be with the suffering and to not run away from it. And he’s like, yeah, but… And then the mind creates all these excuses and all of the brothers are like, no, no, we can remove that responsibility from you. We will give you the healing place you need. Will he give himself permission to lean into that? So for me, like, I know that the sangha is always there. That’s a fact. But am I ready to lean in to it? Because there’s something that’s very humbling about that. And especially the older you become, there’s a lot of pride in that, to lean and say, sangha, I suffer, help me. Jo, I suffer.

01:21:56

Me too. One of the things I’m hearing in the background, this is about courage, about what it is to be courageous, to be honest about our suffering. And Jo-ann, you talked about the shame and the guilt we sometimes have. So we just feel that we have to hide it. And I remember as you were talking, brother, about being asked to, when you were suffering to give a Dharma talk, I remember once when… I was at The Guardian, and I was giving one of the keynote speeches at London Climate Week. So it’s in front of several hundred people. And I’d had a really difficult experience that morning. And I was feeling really worthless. I was really feeling sort of brow-beaten. And I showed up to this conference. And you know, you have to sit in the front row, reserve seating. And I as like fourth in the row to speak. And I just thought, what am I going to do? I just wanted to run away. And when they called me up, I just told them how I was feeling. I just said, I’m feeling really worthless. I feel like I’m not making a difference in life. And then shared it within the collective suffering of the climate community of feeling that too. And a lot of people came up and thanked me because for me at that moment, it was a courageous act because I could have run away or I could’ve just done a sort of very general speech. But I chose to share my suffering, but not be a victim of it. And I think one of the things you mentioned about joy, and this has been coming up a lot for me and actually I showed in our new book is, you know, I spent a long time, and I think comes to what you were saying, Jo-ann, sitting at the edge of this ocean of suffering, feeling my duty was to sit at the end of the ocean of suffer and be present for it. And I’ve realized more recently, that I can sit next to the ocean of joy. You know, if there’s an ocean of suffering, by its nature, there’s an ocean of joy, and if we just look at one thing, then actually we’re lost. We’re actually, if we’re able to see there’s an ocean of joy and an ocean of sufferance, they are interconnected, they do rely on each other, then we can sort of find some balance. Jo-ann, I want to come back to you. Because I’ll tell you what was on my mind, and I know you may not answer it, because we’re getting to know each other a bit, but I’m wondering what, on a personal level, what this has done for you, in your life. Because… And the reason I ask it, because how old are you, if you don’t mind me asking?

01:24:42

79.

01:24:42

79. So when I first saw Jo-ann, and dear listeners, you won’t be able to see this, but she has the sparkliest eyes. You know, there’s depth there, there’s brightness… They’re so alive, which tells me something. And I wanted to ask you, should you choose to answer it or not, through all this work, given what you described about your life journey and about your family and the collective suffering, how you are. How this work has supported you, how would you describe your place on this journey?

01:25:25

Well, I think since I’ve been able to see our practice more through a neuroscience lens and let go of more of the shame and self-judgment, much more compassion for myself has come up. And I also see that while I have a pile of shortcomings, we all do. And that made it so I could see myself in a more whole way. And I was thinking that when you were talking, Brother Phap Huu, about what it’s like for monastics, I was thinking in the parallel of, well, we’ve just had a one-week retreat. It’s really just a drop in the bucket. But what happens in one week? We’re divided into little families. And they’re not so little, actually, they’re like 20, 25 people. And so we do the same schedule as everybody else. But then we have a little bit of work. And maybe every day or every other day, we do the work together. And our job on this was to clean up after meals. And so then we get together another three times to share with each other. And we get another couple of times to have dinner. And then we get together another couple of times to create some silly little offering at a talent show, at the end. And so I am not just me, the person with the jacket. I’m also me who’s tempted to lick off the peanut butter spoon when I have to clean it up. Or that person over there isn’t just a neurobiologist, itty-bitty woman, but she’s carrying these great vats of water. And we’re seeing each other in so many different dimensions that our perceptions of each other fall away. And I think there might have been a lot of energy in a science retreat with famous scientists to posture ourselves and let everybody know what we got going. But over the sink, that falls away. You know, this famous scientist is scrubbing away and he didn’t get all the pots clean and I had to give it back to him. So then I get to see, oh, this guy’s really humble. He just accepted it, so lovely. And then I just felt so open to him. That’s a collective healing and an individual healing all at once. And then if you stay two weeks, you get so many more opportunities to bump up against rough edges. And they’re like magic if you do it. If you don’t do it, you leave just more disgruntled. So that was kind of a tangent. I was hoping… Well, you ask, what has this done for me? So that’s one thing. I think that a combination of humility and compassion is more alive in me. And I’m kind of crusty person. I’m not a…

01:29:45

I’ve noticed.

01:29:49

Boo. But my soft parts are so much more accessible and…

01:30:02

I noticed.

01:30:06

I’ve learned how to let go of my judgments and care much more deeply, really care. And you were talking about… Well, you had the courage. And you are also, Phap Huu, talking about the courage to do these things. I don’t necessarily think that it’s courage. I think that there’s something underneath. There’s such a deep caring that a person develops that it makes the scary part less important than serving, than bringing forth your authentic self. Those are moments, and it’s cyclic. It’s like, the more you care, the more courage you have, the more goodness you can manifest, the more you care. And the more… It just goes on and on. And so I wondered in that moment that you were fessing up to your despair in the climate conference. What was the courage built on? What was really moving you? I don’t know whether you want to…

01:31:37

I love the way you turn the tables on me. That’s wonderful. I think I was doing it because I had been developing a capacity to be vulnerable and to be prepared to be humiliated. In the sense of the courage for me is the courage to show our wounds rather than hide our wounds. And so in that moment it felt like… So much of what I’ve seen in the world is about that things change when we give permission. And you talked about this with the paper bag, that there was a permission given. And when the permission is given, then people feel they can enter that space. And I know that at a lot of these conferences, the despair is hidden. And it’s wrapped up in an intellectual curiosity or a we can do this or we can that. And I felt in that moment that I was raw and I could offer my rawness to them and break through the intellectual boundaries and go to the heart of what it was about and go the heart to our humanity.

01:32:56

And was that a sense of freedom for you?

01:33:01

Yes, it was because to hide it was more painful than to offer it. And that is the training.

01:33:13

Yes.

01:33:14

And I think Brother Phap Huu is amazing around this.

01:33:19

Am I? Amazing around what?

01:33:21

No, you’re because it would be very easy for Brother Phap Huu to play the abbot card and to be the teacher and to sort of to tell people how it’s done. And week after week, he shows up, all of Phap Huu shows up and I think one of the reasons people appreciate this podcast is because of we show up as we are, with our wounds. And if we need to cry, we cry in… And we share, we offer up our hearts. And when you offer up your heart, then other people resonate, as you said. And then they’re able to offer up their heart and that’s what changes the world. It’s not an intellectual discussion. See, I answered your question.

01:34:15

I want to give a little more answer to your question.

01:34:21

I’d love you to.

01:34:23

In writing my book, I went through quite a bit to help people understand how to stabilize their nervous system and to see it through the eyes of our practice. But then it occurred to me, and this is an experience I’ve had many times. There’s a time in the kitchen when we’re all on rotation and we’re making a meal. And we’re doing it in pretty much silence. And I’ve got a big pot of something and I’m trying to get it over there. And somebody just comes along and picks it out of my hands and puts it there. That there’s a sense of a flow of protoplasm or something where you really get a sense of you are just a cell in the sangha body. That you’re part of an organism. And it got me into curiosity if the first part of my book is about how we can regulate our nervous systems and how to know when our nervous system is dysregulated. Then when we’re working as a collective, what does it mean to be regulated or not regulated? And what are the skills and the practices that help us regulate the collective? So that’s a whole other area that I think that laypeople have the opportunity in sanghas to, if you’re in your sangha for a goodly period of time, that you get to know people at such a depth that you can begin to talk, you can have a courage to speak up and say, you know, I think it’s time for us to do something where we have more vulnerability to deepen. Now I’m like off on a tangent on the word deepen as well.

01:36:51

You’re allowed to go off on a tangent.

01:36:53

Well, I think there’s so many people who come and they come to a question and answer and inevitably somebody says, please tell me how can I deepen my practice? And that they’re thinking that they are going to be in one of these lovely altered states. And that becoming vulnerable like you said and really telling your truth is how we deepen our practice, how we stretch ourselves, how we take risks and that we invite others in our sangha to do that when we do it, when we do as an example rather than as a forcing. And that sanghas that stay together and they can absorb new people but there’s a level of intimacy and understanding and acceptance. Okay, this person goes off for too long and this one makes assumptions but there’s so much more to them that we experience and that this practice is a sangha-based practice. It’s not a sitting-based practice where we’re gonna sit many, many hours a day. We’re going to rub up against each other and see how our suffering is made right in that moment. Not something that happened 10 years ago that happens to be coming up. It’s actually coming up right here in the dish water and you know we can trace it back and that’s beneficial as well. But we can also learn how to get along with each other at the dish pan. And then, for lay people, we go home and we take that understanding and we see how it’s directly applicable. We don’t have to be sitting on the cushion for long hours.

01:39:16

Brother Phap Huu, this is something that you keep coming up against in Plum Village is people come and almost because of what we’ve discussed earlier about the fact of there’s all these expectations for things to happen fast and easy and comfort that people come and expect almost can have even a transactional idea of Plum Village that you come here, you pay your money, and at the end of it you want to come and be healed or come and be better whereas actually the best might be to give people the chance to touch their suffering. Is there anything else you want to mention about that?

01:39:59

Just the words that keep coming up for me is there’s no way to healing. Healing is the way. And that also means that the healing can take some time. So there is a virtue to patience in our understanding of the practice. But not to be blinded by our thinking of to wait for the healing and then to be happy because there’s so much realization that we can touch in this present moment like Jo-ann was sharing, like when you wash the dishes, it’s like that can be the most wonderful moment in your life. And this comes to the miracle of mindfulness. That’s like Thay gave a whole chapter to washing your dishes in his book The Miracle of Mindfulness. He said, when you washed the dishes just wash the dish. See the water, see the food that you eat and now you can wash the dishes. It’s just there’s so much that can be in the present moment. And that is why our practice is present moment based. Even that healing that we’re looking for in the future is not yet there. But the healing is in the present moment by the acceptance, the awareness of. We say awareness of, that is mindfulness not transformation of. We always start like our trainings as aware of. So it’s very present moment center our Dharma. But in the present moment it embraces the past as well as it is the conditions of the future. So be kind, be patient and know for me that one of the liberation feeling was the healing is happening now. And I think that for me has also allowed me to really touch the deepening of the practice. And I can sit for 10 hours but I can come out more toxic and angry. But I can spend, you know, two hours talking and laughing with everyone and listening to jokes and wholesome jokes of course, and and that is very healing. You know, there’s so much to healing that we all can tap into. And in one of the retreats in this year also there was one Dharma family and every time I walk past, it wasn’t my Dharma family, they just laugh. One of them said, I’ve never laughed this much in my life. And who would have thought that coming to a Buddhist monastery…

01:42:47

And a science retreat.

01:42:49

I would be experiencing this. So the name of the retreat was the Wonder of It All. Or that’s it, right? The wonder of it all. And so there’s so much wonder in the very here and now. And to not be caught in when we go down the path of healing or path of practice path of enlightenment to think that that is it. This is it is whatever we are doing in the present moment.

01:43:18

Thank you, Jo-ann, for joining us today. The wonder of it all, just this present moment. And just, dear listeners, just to say that Jo-ann mentioned her book. Her book is called Unshakable and it’s published by Parallax Press. And actually I think brother, our new book Calm in the Storm, ways to cultivate stability in an anxious world is a good accompaniment to Jo-ann’s book because actually they’re both looking to help people in this modern world where there’s so much movement so much overwhelm so much of shaking our nervous system that it’s so important to find ways to come back to ourselves to calm ourselves, to be present, to be joyful, to be in community and to express love for each other. Thank you both.

01:44:19

Can I give a plug for Embrace?

01:44:21

Yes.

01:44:22

Absolutely.

01:44:22

So we have a sangha that offers study groups to Plum Village practitioners to be able to go through the book Unshakable and to get a real felt sense in community of the various practices that we do in Plum Village and to see them through that neuroscience lens to help fill in some of the gaps like what does it mean to be carried away and how can, why is beginning anew helpful for the nervous system and how is it a collective healing and that kind of thing.

01:45:10

I love that. And how do we find out about it?

01:45:12

We have a website which is EmbraceSangha.org very simple and we offer a variety of study groups.

01:45:24

Amazing. Thank you, Jo-ann, for doing this.

01:45:28

Indefatigable, Jo-ann. What a beautiful spirit. I know it’s not you. I know.

01:45:34

It’s really an organism that the Embrace has developed as a very self-organizing wonder.

01:45:45

Beautiful. And Jo-ann, thank you so much.

01:45:53

So, dear listeners, we hope you feel soothed by this episode. If you want to listen to more episodes of The Way Out Is In, you can find us on Spotify, on Apple Podcasts, on other platforms that carry podcasts and also, not forgetting, our very own Plum Village App.

01:46:18

If you like what you are hearing, you can also subscribe to the podcast and you can leave a review because it helps inspire others to discover this podcast. You can also find all previous guided meditation in the On-the-go section of the Plum Village App. So sorry for not doing a guided meditation for today because the conversation was so rich and we have a guest with us. The podcast is co-produced by Global Optimism and the Plum Village App with support from the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation. If you feel inspired to support the podcast and the community moving forward, please visit www.tnhf.org/donate and we really would like to offer our gratitude to our friends and collaborators, Clay, aka The Podfather, our co-produser, as well as Cata, our other co-producer. Our other friend, Joe, who is on audio editing. Today, Georgine, on sound and engineering. Anca, our show notes and publishing. Jasmine and Cyndee, our social media guardian angels. And to all of you for joining and listening. We will see you next time. Thank you.

01:47:40

The way out is in.